Design Matters in Defense

This is the first in a series of articles exploring how human-centered design can transform mission-critical systems. In this effort, I will share ideas, lessons, and examples from the field, and I hope they spark meaningful thinking about the role design can and should play in defense.

When I first began my career, I never imagined I would one day be working on defense products. My background is in graphic design, and early in my career I was focused on branding, corporate identity, and visual communication. Like many designers of my generation, I quickly moved into web design as my clients all wanted a web presence. That shift introduced me to technology-focused projects, and before long I was designing what you might call light web applications. The added complexity fascinated me. I loved the problem solving, the challenge of structuring information, and the opportunity to design for more than just visual communication.

That curiosity and desire for complexity carried me into product design more fully. I joined Frog Design, where I cut my teeth on methodologies and approaches for design research, interaction design, and deepened my skills in visual design for technology-driven projects across industries. After a short stint in-house with Microsoft, I came back to consulting. This time at Teague, where my focus was sharpened on enterprise and B2B systems which transitioned well into products for high-stakes environments. Defense work quickly became not just part of my portfolio but a clear path where my skills and interest feel most relevant.

The Pressure of High-Stakes Environments

I have come to believe that design in defense has to focus on three things above all: clarity, trust, and speed.

Clarity means stripping away unnecessary noise so the system operator sees what matters in the moment. Trust means creating systems that behave predictably and give operators confidence that what they are seeing is accurate and understandable. Speed means designing for reduced hesitation, supporting decision-making when seconds make a difference.

I think of these principles not as ideals but as operational requirements. In the commercial world, a confusing interface might mean a customer gets frustrated and abandons a purchase. In defense, confusion might mean a delayed decision, a misidentified signal, or a failed mission. The stakes are entirely different. That is why design here cannot be treated as a decorative layer at the end of engineering. It must be present from the beginning as part of the core strategy and development.

A Few Lessons From the Field

The most powerful insights I have gained in defense design have come directly from the people who use the systems. I’ve found that warfighters often cannot exactly describe product concepts abstract terms. But when shown concepts, they have very precise feedback, and are eager to give it.

During one evaluation, every soldier using our prototype felt strongly that our design had prioritized entirely the wrong information on the primary screen and the most critical information on the secondary screen. This insight completely changed our interaction model for the better. An insight we would have never known without the input of active warfighters.

In another project, I saw decision-making time reduced from eleven seconds to three after our interface redesign clarified visual priorities and removed unnecessary steps. That improvement was not about adding capability. It was about reorganizing information, creating clear actions, and incorporating modern interaction patterns that were intuitively, even under stress. Seconds saved in those environments matter.

I have also seen the opposite: systems so complex and outdated that operators simply refused to use them as intended. Instead they resorted to civilian options—despite being against orders—rather than dealing with the hassle. That is a design failure with real operational cost; especially, when considering near-peer conflicts. Those experiences fuel my conviction that design in defense is not optional. It is critical.

Building on a Successful Approach

My approach combines well-established design frameworks with minor adaptations for the defense environment.

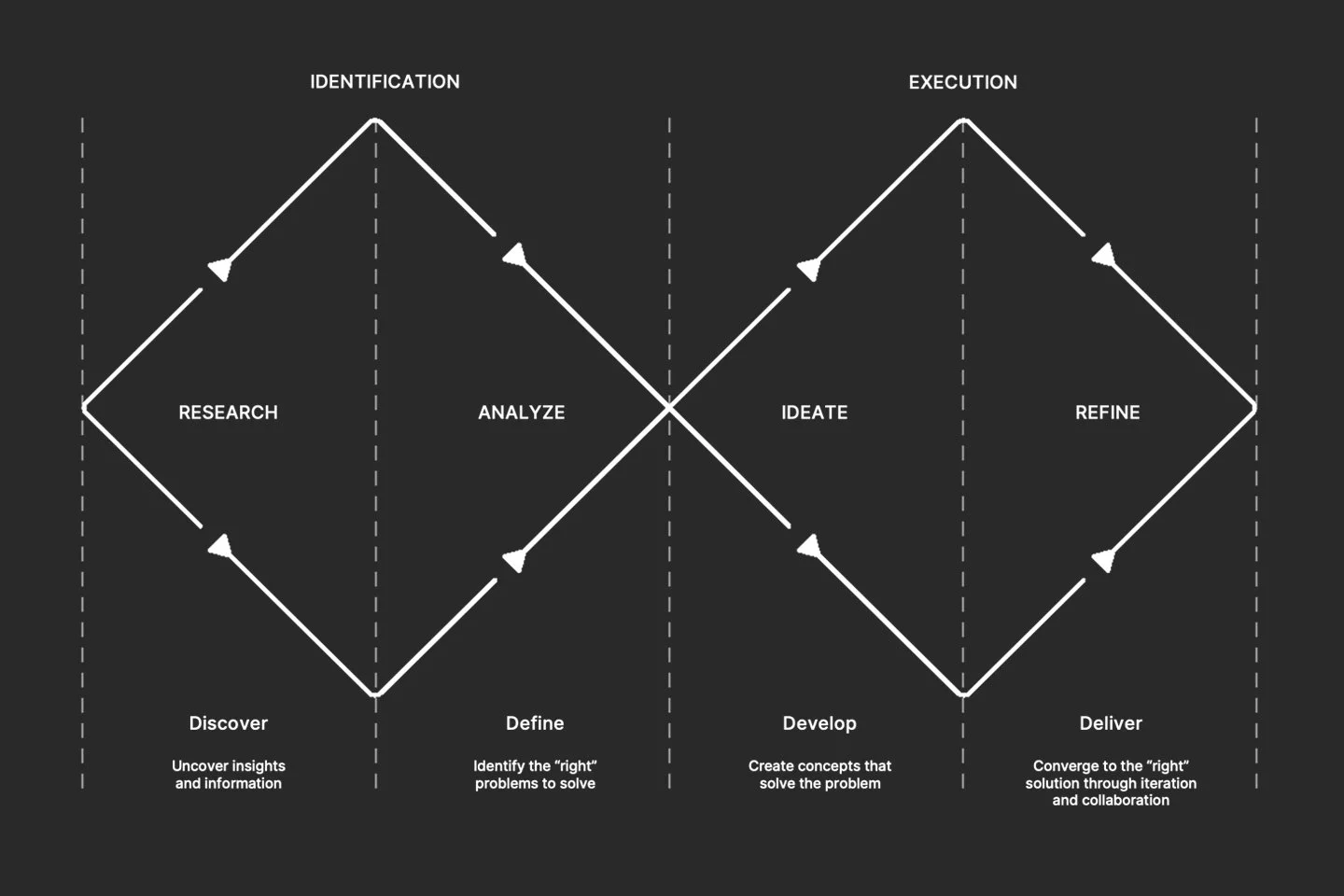

The Double Diamond model is a popular framework developed to approach complex problems in four phases: Discover, Define, Develop, Deliver. Discovery involves broad exploration to understand the problem space and gather insights from target users and product stakeholders. Definition takes those learnings and synthesizes the information in opportunities and defines the core problem to be solved. Development is about generating a range of potential solutions which may take a variety of forms from low-to-high fidelity. Delivery involves testing and refining prototypes or builds with end users to determine the most viable designs.

Another framework I use is the OODA loop: Observe, Orient, Decide, Act. This model, rooted in military decision-making, pairs well with UX. Good design supports observation by making data prioritized and visually hierarchical. It aids orientation by providing context and filtering out irrelevant information for a given context. It enables decision by presenting options clearly. And it accelerates action by making execution appropriately frictionless.

The key to unlocking the potential of product development is with design research. These frameworks emphasize iterative design, prototyping, and testing cycles and the necessity to work directly with active warfighters who have firsthand experience with the aspects a product is trying to improve.

In defense, I work across the industry from large defense Primes to emerging startups. Each brings strengths and challenges. Primes have deep domain expertise and established integration processes, but their pace may be slow, often hamstrung by legacy technologies. Startups, unencumbered, move quickly and boldly but may struggle with aligning on a clear strategic vision. My role is to adapt to these environments, identify a successful coarse of action, and partner with my clients and collaborators to overcome challenges by making ideas tangible and creating the right stories to garner both comprehension and buy-in.

Where We Are Headed

After seven years designing for defense, I am convinced of one thing: human-centered design is not a luxury here, it is a necessity. We ask people to operate complex systems in dynamic, high-pressure environments. They deserve tools that are intuitive, effective, and reliable. To do otherwise is to accept avoidable friction, error, and risk.

Younger service members are entering with different expectations. They have grown up with smartphones and consumer technology that is intuitive and polished. They expect defense systems to carry the same level of ease, and they recognize when they do not. This generational shift is building pressure for what defense products and services must deliver.

Looking forward, the rise of autonomy, automation, and adaptive systems will only increase the importance of design. These technologies introduce new complexity and new risks. A range of operators will need to trust them, understand them, and act confidently with them. We can help. Good design makes complexity usable. Great design turns complexity into advantage.

For me, that is why design matters in defense. It is not about how systems look. It is about whether they work when it matters most. It is about clarity under stress, trust in the system, and speed in decision-making. That is why I believe design must have a permanent seat at the table in defense strategy and innovation.

Further Reading:

Teague’s Design for Defense Services: Explore how Teague applies human-centered design to mission-critical systems in the defense sector.

Nielsen Norman Group UX Best Practices: A wealth of UX research, guidelines, and best practices that can be applied to defense systems.

Design Council’s Framework for Innovation: Learn about this framework and how it can be used to guide the design process.

U.S. Web Design System (USWDS): Discover how this design system helps create cohesive, accessible, and user-friendly government digital services.

Usability.gov UX Best Practices: Access a wide range of resources on user-centered design and usability testing.